mirror of

https://github.com/robindhole/fundamentals.git

synced 2025-09-16 22:00:32 +00:00

Adds SOLID-II notes.

This commit is contained in:

308

oop/notes/05-solid-02.md

Normal file

308

oop/notes/05-solid-02.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,308 @@

|

||||

# SOLID principles - Liskov, Interface Segregation, and Dependency Inversion

|

||||

|

||||

## Key Terms

|

||||

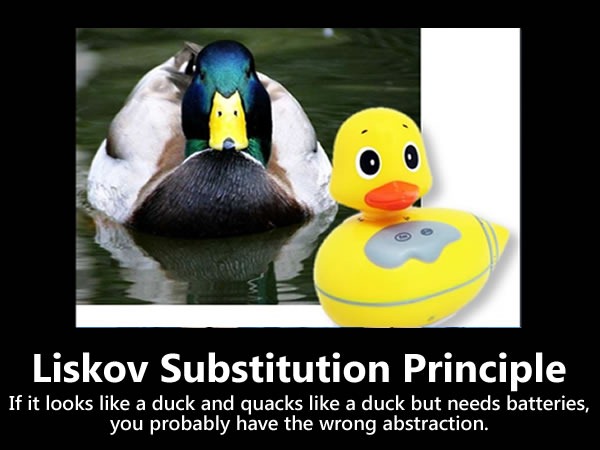

### Liskov Substitution Principle

|

||||

> Objects in a program should be replaceable with instances of their subtypes without altering the correctness of that program.

|

||||

|

||||

### Interface Segregation Principle

|

||||

> Many client-specific interfaces are better than one general-purpose interface.

|

||||

|

||||

### Dependency Inversion Principle

|

||||

> Depend upon abstractions. Do not depend upon concrete classes.

|

||||

|

||||

## Liskov Substitution Principle

|

||||

|

||||

Let us take a look at our final version of the `Bird` class from [the last session](https://github.com/kanmaytacker/fundamentals/blob/master/oop/notes/04-solid-01.md#fixing-ocp-violation-in-the-bird-class). We started with a `Bird` class which had SRP and OCP violations. We now have a `Bird` abstract class which can be extended by the `Eagle`, `Penguin` and `Parrot` subclasses.

|

||||

|

||||

```mermaid

|

||||

classDiagram

|

||||

Bird <|-- Eagle

|

||||

Bird <|-- Penguin

|

||||

Bird <|-- Parrot

|

||||

class Bird{

|

||||

+weight: int

|

||||

+colour: string

|

||||

+type: string

|

||||

+size: string

|

||||

+beakType: string

|

||||

+fly()

|

||||

}

|

||||

class Eagle{

|

||||

+fly()

|

||||

}

|

||||

class Penguin{

|

||||

+fly()

|

||||

}

|

||||

class Parrot{

|

||||

+fly()

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

We have also added a `fly()` method to the `Bird` class. All the subclasses of `Bird` have to implement this method. A penguin cannot fly, yet we have added a `fly()` method to the `Penguin` class. How can we handle this?

|

||||

* `Dummy method` - We can add a dummy method to the `Penguin` class which does nothing.

|

||||

* `Return null`

|

||||

* `Throw an exception`

|

||||

|

||||

In the above methods, we are trying to force a contract on a class which does not follow it. If we try to use a `Penguin` object in a place where we expect a `Bird` object, we could have unexpected outcomes. For example, if we call the `fly()` method on a `Penguin` object, we would get an exception. This is not what we want. We want to be able to use a `Penguin` object in a place where we expect a `Bird` object. We want to be able to call the `fly()` method on a `Penguin` object and get the same result as if we had called it on a `Sparrow` object. This is where the Liskov Substitution Principle comes into play.

|

||||

|

||||

```java

|

||||

List<Bird> birds = List.of(new Eagle(), new Penguin(), new Parrot());

|

||||

for (Bird bird : birds) {

|

||||

bird.fly();

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

This is a violation of the Liskov Substitution Principle. The Liskov Substitution Principle states that objects in a program should be replaceable with instances of their subtypes without altering the correctness of that program. In other words, if we have a `Bird` object, we should be able to replace it with an instance of its subclasses without altering the correctness of the program. In our case, we cannot replace a `Bird` object with a `Penguin` object because the `Penguin` object requires special handling.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

### Creating new abstract classes

|

||||

|

||||

A way to solve the issue with the `Penguin` class is to create a new set of abstract classes, `FlyableBird` and `NonFlyableBird`. The `FlyableBird` class will have the `fly()` method and the `NonFlyableBird` class will not have the `fly()` method. The `Penguin` class will extend the `NonFlyableBird` class and the `Eagle` and `Parrot` classes will extend the `FlyableBird` class. This way, we can ensure that the `Penguin` class does not have to implement the `fly()` method.

|

||||

|

||||

```mermaid

|

||||

classDiagram

|

||||

class Bird{

|

||||

+weight: int

|

||||

+colour: string

|

||||

+type: string

|

||||

+size: string

|

||||

+beakType: string

|

||||

}

|

||||

class FlyableBird{

|

||||

+fly()

|

||||

}

|

||||

Bird <|-- FlyableBird

|

||||

FlyableBird <|-- Eagle

|

||||

FlyableBird <|-- Parrot

|

||||

|

||||

class NonFlyableBird{

|

||||

+eat()

|

||||

}

|

||||

Bird <|-- NonFlyableBird

|

||||

NonFlyableBird <|-- Penguin

|

||||

|

||||

class Eagle{

|

||||

+fly()

|

||||

}

|

||||

class Penguin{

|

||||

+eat()

|

||||

}

|

||||

class Parrot{

|

||||

+fly()

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

This is an example of multi-level inheritance. The issue with the above approach is that we are tying behaviour to the class hierarchy. If we want to add a new type of behaviour, we will have to add a new abstract class. For instance if we can have birds that can swim and birds that cannot swim, we will have to create a new abstract class `SwimableBird` and `NonSwimableBird` and add them to the class hierarchy. But now how do you extends from two abstract classes? You can't. Then we would have to create classes with composite behaviours such as `SwimableFlyableBird` and `SwimableNonFlyableBird`.

|

||||

|

||||

```mermaid

|

||||

classDiagram

|

||||

class Bird{

|

||||

+weight: int

|

||||

+colour: string

|

||||

+type: string

|

||||

+size: string

|

||||

+beakType: string

|

||||

}

|

||||

class SwimableFlyableBird{

|

||||

+fly()

|

||||

+swim()

|

||||

}

|

||||

Bird <|-- SwimableFlyableBird

|

||||

SwimableFlyableBird <|-- Swan

|

||||

|

||||

class NonSwimableFlyableBird{

|

||||

+fly()

|

||||

}

|

||||

Bird <|-- NonSwimableFlyableBird

|

||||

NonSwimableFlyableBird <|-- Eagle

|

||||

|

||||

class SwimableNonFlyableBird{

|

||||

+swim()

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

Bird <|-- SwimableNonFlyableBird

|

||||

SwimableNonFlyableBird <|-- Penguin

|

||||

|

||||

class NonSwimableNonFlyableBird{

|

||||

+eat()

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

Bird <|-- NonSwimableNonFlyableBird

|

||||

NonSwimableNonFlyableBird <|-- Toy Bird

|

||||

|

||||

class Swan{

|

||||

+fly()

|

||||

+swim()

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

class Eagle{

|

||||

+fly()

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

class Penguin{

|

||||

+eat()

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

class Toy Bird{

|

||||

+makeSound()

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

If we want to add a new type of behaviour, we will have to add a new abstract class. This is why we should not tie behaviour to the class hierarchy.

|

||||

|

||||

### Creating new interfaces

|

||||

|

||||

We can solve the issue with the `Penguin` class by creating new interfaces. We can create an `Flyable` interface and an `Swimmable` interface. The `Penguin` class will implement the `Swimmable` interface and the `Eagle` and `Parrot` classes will implement the `Flyable` interface. This way, we can ensure that the `Penguin` class does not have to implement the `fly()` method.

|

||||

|

||||

```mermaid

|

||||

classDiagram

|

||||

class Bird{

|

||||

<<abstract>>

|

||||

+weight: int

|

||||

+colour: string

|

||||

+type: string

|

||||

+size: string

|

||||

+beakType: string

|

||||

|

||||

+makeSound()

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

Bird <|-- Eagle

|

||||

Bird <|-- Parrot

|

||||

Bird <|-- Penguin

|

||||

class Flyable{

|

||||

<<Interface>>

|

||||

+fly()*

|

||||

}

|

||||

Flyable <|-- Eagle

|

||||

Flyable <|-- Parrot

|

||||

|

||||

class Swimmable{

|

||||

<<Interface>>

|

||||

+swim()*

|

||||

}

|

||||

Swimmable <|-- Penguin

|

||||

|

||||

class Eagle{

|

||||

+fly()

|

||||

}

|

||||

class Penguin{

|

||||

+swim()

|

||||

}

|

||||

class Parrot{

|

||||

+fly()

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Since we are not tying behaviour to the class hierarchy, we can add new types of behaviour without having to add new abstract classes. For instance, if we want to add a new type of behaviour, we can create a new interface `CanSing` and add it to the class hierarchy.

|

||||

|

||||

### Summary

|

||||

* The Liskov Substitution Principle states that objects in a program should be replaceable with instances of their subtypes without altering the correctness of that program.

|

||||

* To identify violations, we can check if we can replace a class with its subclasses having to handle special cases and expect the same behaviour.

|

||||

* Prefer using interfaces over abstract classes to implement behaviour since abstract classes tend to tie behaviour to the class hierarchy.

|

||||

|

||||

## Interface Segregation Principle

|

||||

|

||||

Segregation means keeping things separated, and the Interface Segregation Principle is about separating the interfaces.

|

||||

|

||||

The principle states that many client-specific interfaces are better than one general-purpose interface. Clients should not be forced to implement a function they do no need. Declaring methods in an interface that the client doesn’t need pollutes the interface and leads to a “bulky” or “fat” interface

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

A client should never be forced to implement an interface that it doesn’t use, or clients shouldn’t be forced to depend on methods they do not use. In other words, we should not create fat interfaces. A fat interface is an interface that has too many methods. If we have a fat interface, we will have to implement all the methods in the interface even if we don’t use them. This is known as the interface segregation principle.

|

||||

|

||||

Let us take the example of our `Bird` class. To not tie the behaviour to the class hierarchy, we created an interface `Flyable` and implemented it in the `Eagle` and `Parrot` classes.

|

||||

|

||||

```java

|

||||

public interface Flyable {

|

||||

void fly();

|

||||

void makeSound();

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

Along with the `fly()` method, we also have the `makeSound()` method in the `Flyable` interface. This is because the `Eagle` and `Parrot` classes both make sounds when they fly. But what if we have a class that implements the `Flyable` interface? The class does not make a sound when it flies. This is a violation of the interface segregation principle. We should not have the `makeSound()` method in the `Flyable` interface.

|

||||

|

||||

Larger interfaces should be split into smaller ones. By doing so, we can ensure that implementing classes only need to be concerned about the methods that are of interest to them. If a class exposes so many members that those members can be broken down into groups that serve different clients that don’t use members from the other groups, you should think about exposing those member groups as separate interfaces.

|

||||

|

||||

Precise application design and correct abstraction is the key behind the Interface Segregation Principle. Though it'll take more time and effort in the design phase of an application and might increase the code complexity, in the end, we get a flexible code.

|

||||

|

||||

## Dependency Inversion Principle

|

||||

The principle of dependency inversion refers to the decoupling of software modules. This way, instead of high-level modules depending on low-level modules, both will depend on abstractions. If the OCP states the goal of OO architecture, the DIP states the primary mechanism for achieving that goal.

|

||||

|

||||

The general idea of this principle is as simple as it is important: High-level modules, which provide complex logic, should be easily reusable and unaffected by changes in low-level modules, which provide utility features. To achieve that, you need to introduce an abstraction that decouples the high-level and low-level modules from each other. Dependency inversion principle consists of two parts:

|

||||

* High-level modules should not depend on low-level modules. Both should depend on abstractions.

|

||||

* Abstractions should not depend on details. Details should depend on abstractions.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Our bird class looks pretty neat now. We have separated the behaviour into different lean interfaces which are implemented by the classes that need them. When we add new sub-classes we identify an issue. For birds that have the same behaviour, we have to implement the same behaviour multiple times.

|

||||

|

||||

```java

|

||||

public class Eagle implements Flyable {

|

||||

@Override

|

||||

public void fly() {

|

||||

System.out.println("Eagle is gliding");

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

public class Sparrow implements Flyable {

|

||||

@Override

|

||||

public void fly() {

|

||||

System.out.println("Sparrow is gliding");

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

The above can be solved by adding a default method to the `Flyable` interface. This way, we can avoid code duplication.

|

||||

But which method should be the default implementation? What if in future we add more birds that have the same behaviour? We will have to change the default implementation or either duplicate the code.

|

||||

|

||||

Instead of default implementations, let us abstract the common behaviours to a separate helper classes. We will create a `GlidingBehaviour` class and a `FlappingBehaviour` class. The `Eagle` and `Sparrow` classes will implement the `Flyable` interface and use the `GlidingBehaviour` class. The `Parrot` class will implement the `Flyable` interface and use the `FlappingBehaviour` class.

|

||||

|

||||

```java

|

||||

public class Eagle implements Flyable {

|

||||

private GlidingBehaviour glidingBehaviour;

|

||||

|

||||

public Eagle() {

|

||||

this.glidingBehaviour = new GlidingBehaviour();

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

@Override

|

||||

public void fly() {

|

||||

glidingBehaviour.fly();

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Now we have a problem. The `Eagle` class is tightly coupled to the `GlidingBehaviour` class. If we want to change the behaviour of the `Eagle` class, we will have to open the Eagle class to change the behaviour. This is a violation of the dependency inversion principle. We should not depend on concrete classes. We should depend on abstractions.

|

||||

|

||||

Naturally, we rely on interfaces as the abstraction. We create a new interface `FlyingBehaviour` and implement it in the `GlidingBehaviour` and `FlappingBehaviour` classes. The `Eagle` class will now depend on the `FlyingBehaviour` interface.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

```java

|

||||

interface FlyingBehaviour{

|

||||

void fly()

|

||||

}

|

||||

class GlidingBehaviour implements FlyingBehaviour{

|

||||

@Override

|

||||

public void fly() {

|

||||

System.out.println("Eagle is gliding");

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

...

|

||||

|

||||

class Eagle implements Flyable {

|

||||

private FlyingBehaviour flyingBehaviour;

|

||||

|

||||

public Eagle() {

|

||||

this.flyingBehaviour = new GlidingBehaviour();

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

@Override

|

||||

public void fly() {

|

||||

flyingBehaviour.fly();

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

## Reading list

|

||||

* [LSP](http://web.archive.org/web/20151128004108/http://www.objectmentor.com/resources/articles/lsp.pdf)

|

||||

* [SOLID - Recap](https://www.cs.odu.edu/~zeil/cs330/latest/Public/solid/)

|

||||

Reference in New Issue

Block a user